In this issue:

- Zoning Change Hearings a Greek Tragedy

- Our Testimony on ZQA

- All About the New Streetcar

- Coalition to Save Chinatown and Lower East Side Rallies at Gracie Mansion

- Cartoon of the Week

- The “Why Don’t We Have One of These” Award goes to…. The Fed’s “Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative”

- Who Owns the Sunlight? A long-form op-ed

Zoning Change Hearings A Greek Tragedy

The architectural-real estate alliance testifies….

When a city cannot overcome it worst characteristics, in this case the capture of politicians and regulatory agencies by real estate interests, when it becomes clear that such a problem is causing the city to take a path of self-destruction, a simple public hearing feels like a Greek tragedy.

Last Tuesday and Wednesday (Feb 8th & 9th) the City Council held day-long hearings on the two proposed zoning text amendments, dubbed ZQA (a massive city-wide height increase) and MIH (affordable housing requirements). Hundreds turned out to testify, largely in opposition to ZQA, as the community boards across the city already voted no. Highlights:

- Five people from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation undercut the logic behind the claim of real estate developers that they must have more of building envelope to create higher ceilings on ground floors. Using survey data from their neighborhood, they found this not to be true in the slightest, that developers were choosing not to build high-ceilings for their ground floor retail spaces when they easily could have done so, even when they had the extra envelope to do so.

- Many people from around the city spoke eloquently that there has been insufficient consultation with communities and that the “one size fits all” character of the proposals was an immense, generational mistake. Every neighborhood needs its own plan. The council did not seem too interested in that idea.

- The architecture-real estate alliance (Industrial Complex?) manifested itself big time as the American Institutes of Architects, SHoP Architects, and Marvel Architects proclaimed their support of the zoning amendments, so that they could have more “design freedom” and to make it “easier to make huge glass windows across steel beams on the ground floors” [sic]. Even cynical Councilman David Greenfield seemed to find this self-interested testimony hilarious, as evidenced by his chuckles and smiles as the architects spoke.

- Moving testimony was given by LANDMARK WEST! and can be found here. LANDMARK WEST! was one of many who pointed out the poisonous, gaping loophole in the new proposed zoning rules: all developers have to do is plead “hardship” before the developer-owned Bureau of Standards and Appeals, and bingo, they would be off the hook on affordable housing. The public’s collective eyes were rolling in disgust throughout the room as that message became clear.

- We called for a definition of density and for a range of optimal densities for the city, as well as a new city commission to be appointed to investigate how real estate has corrupted our government. Our testimony is given below. We spoke to the macro issues rather than the ZQA/MIH details that have been amply treated by others.

![]()

Our Testimony on ZQA

Councilmember Andrew Cohen of the Bronx, one of the few to ask good and pointed questions.

Testimony

Everything is backwards. Before New York gives FAR to developers in exchange for elusive public benefits, we need a meaningful environmental impact statement, not the shameful hack job that was done for ZQA and MIH. There are other reforms too that require debate and action before doing something as big as ZQA and MIH. Here are some.

- We need height restrictions contextual and specific to neighborhoods with limits on transferable development rights. This is compatible with growth and a human-scale build-out of the city. It is simply not true that you need high-rise to have high-density.

- Rising above the cornice line should require an environmental impact statement that looks at the cumulative, city-wide damage to neighborhood character and the social costs of privatizing public views and sunlight.

- If a neighborhood undertakes a legitimate planning process, there must be law that obliges the Council to vote upon it.

- We need a new rule or law about density and livability. There is density that is too low and could turn cities into suburbia. There is density that is too high and turns great neighborhoods into high-rise wastelands. So what is a “just right” range of densities for a livable city? We must have this public debate.

- The claim that density can only be put where there are existing subway lines – because the city can’t help car-dependent areas – is a failure of both vision and government. It’s also an obvious lie when the city now pushes an expensive streetcar for the Brooklyn waterfront while ignoring the car-dependent periphery.

- How else might we get affordable housing without big developers? That discussion has been too short. For example: we have 1 million single and two family homes in New York City. If just 20% of those homeowners built safe apartments in attics, basement, and garages, it would add 200,000 new affordable housing units at the bottom-end of the market – without ripping apart our city. It would also benefit the middle class. Why is this not under discussion as a major policy initiative?

- And because the process and rules of the zoning game are so biased, we need a city version of the Moreland Commission on Corruption to study how big real estate interests have captured public policy on anything to do with zoning or our built environment. The initiative for zoning reform should be coming from residents, not the real estate lobby.

After these reforms have seen widespread public debate and legislative action, then would be time to re-consider MIH. ZQA needs to be dropped totally.

![]()

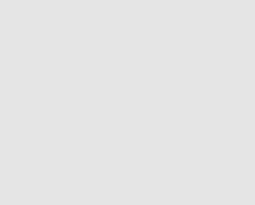

All about the New Streetcar- Apparently it is not as cool as it sounds….

In reaction to the recently announced Brooklyn Queens Connector streetcar, wonks and pundits have pointed out the lack of information and planning that went into developing the $2.5 billion boondoggle and quaqmire. The streetcar would run along the Brooklyn waterfront. It is backed mainly by developers who feel that the waterfront properties they own would be better served with a street car that runs parallel to three existing subway lines.

Critics have been quick to point out that the streetcar does not appear to connect to any existing subway stations, making transfers difficult and possibly lowering the number of daily users. In addition, as pointed out by John Orcutt in the Daily News, the nations fastest streetcars, in Portland and Seattle, run at only 9.9 and 5 mph respectively. Many reporters have walked faster than the streetcars in their cities, yet de Blasio remains adamant that his streetcar will relieve congestion. Adding another form of transportation to already crowded streets, especially one that cannot change its route or move around obstacles, seems to add to a perplexing congestion issue.

So where did this idea come from? The Friends of the Brooklyn Queens Connector, “made up of transportation experts, urban planners, and developers with real estate interests in the area – have developed the plan.”

There are other transportation options proposed but they have been continuously shot down. Increasing bus and bike lanes would be cheaper and more effective, yet in this case innovation has been valued over efficiency. In addition, critics point out that the Second Avenue Subway remains behind scheduled and its second leg unfunded. The Port Authority bus station has not been fully renovated since the 1950’s.

A round-up of streetcar criticisms:

- In an incredibly well put-together and researched opinion piece, this article by Jon Orcutt raises all the questions de Blasio should be asking himself as he moves forward.

- Addressing the issue of the streetcar as a gimmick, this article also highlights the fact that de Blasio avoids negotiating with Governor Cuomo by bypassing the MTA.

- Providing a stark map of car-dependent areas and a visual representation of the small impact the streetcar would have, this post by Streetsblog is a great tool for understanding the proposal and for asking the question: why aren’t we helping the car-dependent areas of the city?

- Speaking with a former Portland politician, this article looks at the numbers proposed by de Blasio and contrasts them with the actual usage Portland saw after the introduction of a streetcar in 2001.

- Proposing simple questions in response to the streetcar plans, this article addresses how the project will be paid for, what the market for potential riders would be, and the issue of building a streetcar on a floodplain.

![]()

Rallies Continue at Gracie Mansion

The Coalition to Save Chinatown and the Lower East Side will be holding one of its on-going rallies at Gracie Mansion at East End Avenue and 87th Street, this Thursday, Feb 18, at 4:30 p.m.

What do they want? Approval for their community plan and justice for their neighborhood.

![]()

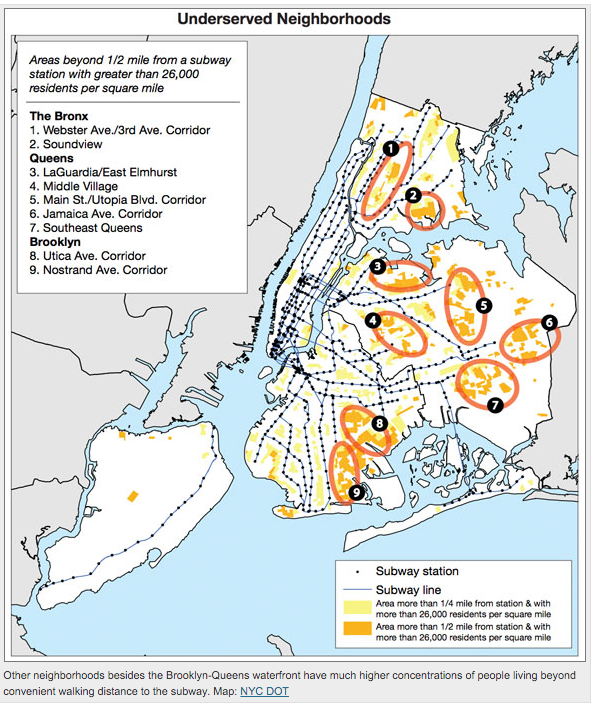

Cartoon of the Week

The ZQA hearings were often so slow and boring I had to entertain myself with a book, this time, “Shaping the City” by the brilliant Gregory Gilmartin. One of the illustrations was a Roz Chast cartoon, given as a gift to the Municipal Art Society long ago.

![]()

Why don’t We Have a “Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative” Here in New York?

In a New York Times article here we learn that there is a wonderful joint initiative of the Justice Department, Homeland Security, and the F.B.I.. It is hilariously titled, “Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative“. I could not imagine a better name. The staff behind that initiative try to get the goods that dictators have hidden here in the U.S. and return the value of the stolen assets back to the people of the pillaged countries in question.

But hey, we need that right here in River City! Big Real Estate here constitutes a giant kleptocracy, stealing our public assets of sunlight, viewscapes, neighborhoods, and our once great street-level urbanity. We want all those things back! That is exactly what the City Council needs to do, set up a city version of the Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative.

Who Owns the Sunlight?

or, “Why we need height limits”

a long-form op-ed

by Lynn Ellsworth

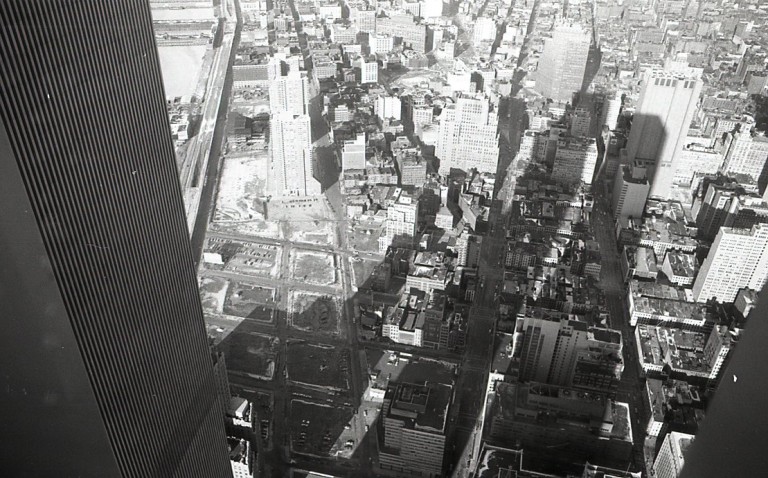

Photo by Geraldine Pontus of skyscaper shadows over the old Washington Market area in the 1970’s. There are now three times as many towers shadowing the same area.

From time to time shifting views about justice cause societies to change the rules of the game for business. Such shifts are provoked by concerns over the social costs of a technology, realization that a resource is no longer abundant, or because society puts a new value on something they once ignored. For example, we once imagined fish were in unlimited supply. Then overfishing drove a few species to near extinction. Luckily, we woke up and changed the rules. Now fishermen have quotas for the catch of particular fish. Certain nets are outlawed. Someone monitors the fish. It’s not a perfect system, but the fisheries are now a managed, regulated public asset instead of an unregulated “free for all.” Scientists now give us a reasonable probability that our grandchildren will know what a lobster looks like. Years later, most people see this kind of rule change as a normal way to solve problems. But at the time of the change, the new rules for sharing the catch seemed odd, even outlandish. Many fishermen hotly contested them.

Here in New York City we have a similar problem, but the disappearing catch is not fish. Instead, we are losing sunlight, sky, street-level viewscapes, and the experience of great urbanity in our low and mid-rise neighborhoods, notably the ones in our city’s historic centers (Sassen 2015). These thing are all public assets. Economists call them common-pool resources (Poteete, Janssen, and Ostrom 2010). They are public goods, a kind of natural capital. But be the asset fish or sunlight, the solution is similar: we must decide as a society to end the free-for-all use of them and co-operatively manage them better.

While some old school academics used to argue that common-pool resources should be privatized entirely (Hardin 1968), we now know that’s very old school: things with common-pool characteristics continue to be well-managed all over the world. Nonetheless, in urban areas some still argue we should ignore the public value of these assets in the name of new high-rise housing (Chakrabarti 2013; Furman Center 2015). But that argument uses a discredited premise that goes like this: the only way to have dense cities it to have high rises. But even the most casual of thinking reveals that position to be nonsense. Empirically speaking, high density does not imply high rise.

Here, I argue that high-rise housing privatizes and undervalues our public assets. It constitutes a takings from the public realm. Just like the case of overfishing by private fishermen, high-rise development literally gives our public assets away to developers. And the housing they produce does not obviously outweigh the long-term losses.

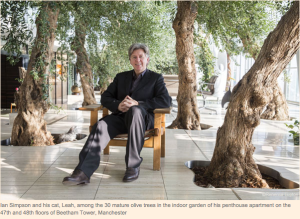

One of the few architects of skyscrapers who chooses to live in one, Mr. Simpson also mitigated the effect by importing an entire forest of olive trees into his penthouse, effectively privatizing access to nature itself.

So you might ask: who does own the sky, the sunlight, and ever-scarcer views of rivers, trees, grass, and parks, or even the views upon beautiful things like the ever-scarcer historic architecture or landmarks in our city? Is it only the rich in their penthouses, like the gentlemen in Figures 2 and 10 (Sunyer 2013) ?

And come to think about it, who owns the kinetic joy of walking on the sunny side of the street in a human-scale neighborhood with its random delights that include small shops, handsome façades, the old wooden doorway and the upward glance to notice for the first time a great landmark like the Public Theatre?

Taylor Swift, New York’s official Ambassador, decidedly prefers the sunny side of the street, as most of her p.r. photos reveal.

The answer is simple: these five assets belong to all of us. Three of them are physical – sky, sunlight, and views onto nature itself. Scientists now tell us – and our common sense agrees – that humans need sky, sunlight and the sight of greenery and water to thrive. We need them for our physical health and even, as we have learned, for our very happiness and cognitive functioning (Kent et al. 2009). Our blood pressure lowers, we laugh more, and we are kinder to others when we have sunlight. People who work in natural sunlight are also more productive than those who work in artificial light. The problem then, is how to keep these assets within a city and how to share them equitably with everyone.

The other two assets are cultural. One would be shared public view corridors toward structures most consider “beautiful” or “landmarked” (as opposed to something merely big). The other cultural public asset would be the kinetic, shared experience of a great, rather than dreary, street level urbanity that connects us to our other public assets, our history, and to each other. We need these in order to have a vibrant public realm in the city – which is another way of describing great urbanity.

The kinetic experience at street level of great urbanity.

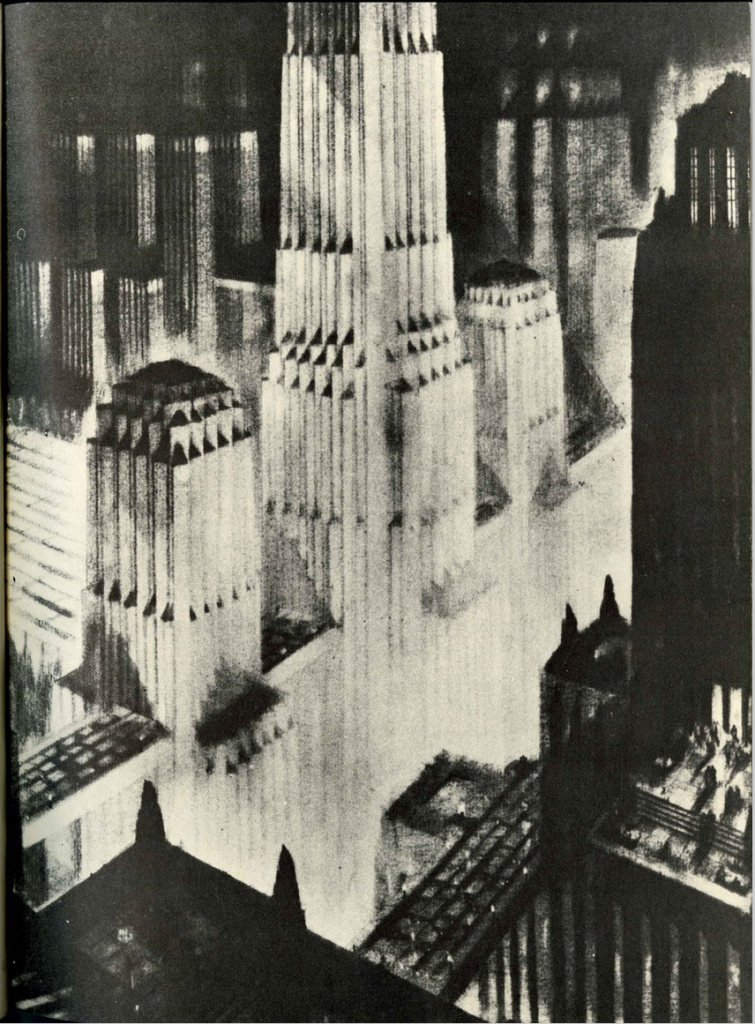

Greatness in the public realm allows us to claim that we are an urban civilization worth emulating, one that people want to live in, claim ownership of, and pass on to their children rather than merely endure until a better opportunity arises. And part of our public realm is the street, and the street really matters. It is where we share sunlight, views, historic architecture, and great urbanity. Because of that, we should be worried about the way we have allowed so many New York streets to fall into permanent shadow. It suggests dark things about the nature of our society and democracy, a darkness that we should not be continuing. Remember the film Bladerunnner? In that oligarchic dystopia the wealthy lived in the sunlight at the top of the towers. They used flying machines to travel without touching the ground. Everyone else lived in darkness at street level. That future is not so far away.

Municipal Art Society’s renderings of what is coming up on 57th Street.

Therefore we must protect our ever-scarcer public commons by better regulating its use. We also must commit to equitable sharing of these assets across generations. Our grandchildren should know what great, human-scaled urbanity is and how it includes sunlight, beauty, history and public spaces like schools, hospitals, and libraries. The trouble we face is that our city government is doing the opposite. It says to developers: come and get it! Free public stuff! Winnings to whoever can grab the most with the biggest fist! Former City Planning Commissioner and real estate developer Joe Rose called the unregulated way builders have been grabbing views and light and sky as “a race to the top.” The result, he said, was “violence to the urban fabric” or in the lingo of economists, a “social cost” and a “negative externality,” all imposed on the public.

Hugh Ferriss’ charcoal drawing of the dark dystopia that the zoning code would bring on. It inspired the joyless world featured in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. It has come to pass in parts of Midtown.

To be sure, there is some law to contend with. In medieval England, there was a bit of common law that said if a man owned a piece of land, he owned the air above it to “the heavens.” But that was before elevators and airplanes made the idea ridiculous, even to the English. And even while it was in force in England, that law shared opposing legal space with the law of “ancient light.” The ancient light rule said: if you could prove that you had sunlight coming in through a window for 20 years, nobody could block that window with new construction. Here in our country, we don’t have an ancient light law, indeed, our legal system does not recognize light as something we can own at present, but much of that is due to a lawyerly confusion. Recognition of sunlight and views as a scarce resource in the public interest is a hardly revolutionary in economics or in the hard sciences, just overdue in the legal world.[1]

Airspace is bit different. To cope with the new technology of airplanes, Congress in 1926 declared that the sky above 500 feet is public domain. Clear enough. Later, the Supreme Court, in an extremely quirky case ready for some challenge, said a country chicken farmer could own the sky up to 83 feet because airplanes needed to fly down to 83 feet to land near his farm. Clearly a rule that needs updating! But that ruling leaves a question: what about the sky between 83 and 500 feet? Is it a no-man’s land? We know it is not. There is no such thing as no-man’s land. It a public commons, an asset that belongs to all.

We can also be creative about laws for this problem. San Francisco has a shadow law. London protects view corridors to Saint Paul’s. Boston has height limits. Santa Barbara has a rule that regulates construction for 100 feet around landmarks. Bhutan measures happiness as a national goal. So perhaps we need a constitutional amendment to guarantee our pursuit of happiness through sunlight?

But before making law, let’s look think harder about what is needed. Although he might have been wrong about his particular zoning reform package, Joe Rose (who was cited above) was right about the race to the top and the consequent violence. Look around. Out-of-context, ludicrously tall luxury condos now hem in our historic districts at every boundary, and soon, every park as well will be cast into total shadow, as has already taken place in Damrosch Park by Lincoln Center and as is now happening around Madison Square.

Free riding on Tribeca’s neighborhood character while simulatneously destroying it’s character. (59 Leonard, photo by Troy Torrison)

The developers of many of these tower condos seduce new buyers to shell out immense sums for the promise of proximity to the ever-scarcer urban experience of living in a “real neighborhood of character,” which is odd when that character is actually low- and mid-rise, and often historic as well. What is really going on is this: the new tower chips away at the quality of the neighborhood with excessive shadowing and the imposition of hyper-density. And the cumulative impact of these towers is devastating. Economists call what developers are doing “free-riding” – benefiting from a neighborhood of character (aka, great urbanity) without paying for it, and even ruining it in the process.

But wait, it gets much worse: new technology is now allowing even bigger, hyper-tall buildings to go up with great speed, to heights nobody imagined possible a few years ago. Think of the new 1000 foot towers arising on 57th Street that are casting shadows onto Central Park. These buildings are all over the city and they cast vast shadows into the public realm beyond that of a single neighborhood. Here too, cumulative impact is ignored.

Towers aren’t all bad. They are a fact of life in many business districts. And an individual skyscraper may appeal to a design fan as an interesting sculpture, especially when approaching the city from the suburbs in a car. And an individual tower might also be loved by millions because it provides selfie backdrops for tourists wandering in double-decker buses. And few deny the breathtaking greatness of the Woolworth tower. But cumulatively the post-WW II skyscrapers so reviled by the critic Ada Louise Huxtable and the cascade of recent towers launched since the Bloomberg-era are destroying our city’s street level urbanity, our affordable housing, and our small businesses. They over-densify a few neighborhoods and under-densify the periphery. A more even-handed distribution of density would better serve two goals: the development of great urbanity at a human-scale and more equitable sharing of resources of sunlight, sky, and view corridors from the street.

The fault lies in the lack of planning about building heights, the excessively laissez-faire attitude about where to put tall buildings, and the refusal to consider their cumulative impact on light, density, public space, and view corridors. City government chooses to ignore the negative externalities that excess density creates, perhaps in their zeal to grow property tax revenue. The fault also lies in the capture of our Landmarks Preservation Commission by real estate interests such that our city never stops allowing historic buildings – usually full of loft-law or rent-stabilized tenants – to be demolished for speculative luxury condos. Even the ancient Romans did it better with their law of 43 A.D. that said, “buildings might not be destroyed for the purpose of speculation in land.” Maybe we need the same law.

Kerston-Europe’s sunlight mirror for Teardrop park in Battery Park City.

And technology will not mitigate the effects of overdevelopment. Mitigation at this scale is impossible and even ridiculous. It also just misses the point, especially when you think of the cumulative impacts. Think of totally shadowed Damrosch Park. And what about the case of the tiny Teardrop Park in Battery Park City? It was built with the full knowledge that it would not have enough sunlight to sustain life. Rather than cut back on the height of the buildings to allow said sun to penetrate, the developer put giant mirrors on top the surrounding buildings so as to redirect sunlight into the canyon where Teardrop sat. No blame to the brilliant landscape designers of Teardrop Park, but mirrors are not a long-term or citywide solution. How do you give back sunlight to an entire shadowed neighborhood? You can’t.

Our city government since the time of the elevator has thoughtlessly squandered or privatized these public resources – so vital to our well-being. Those with something to gain in the current system of privatization repeat over and over the same, evasive, smoke-and-mirror bromides that make no sense: “we can’t keep the city in amber” or “change is inevitable.” They have stuck to that truth-dodging script for so many years with the press repeats them without thinking. Why is the normal, natural, and praiseworthy desire to keep our historic neighborhoods called putting something in “amber”. The word ‘amber’ ultimately is just an insult, not a reality. And in general,“change” needs an adjective or qualifying phrase to be meaningful in public discourse. After all, new human-scale neighborhoods in context with their surroundings in the Bronx would be an example of change for the better.

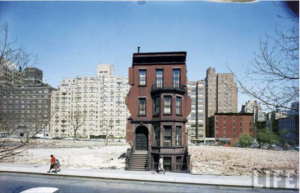

LIFE magazine photo showing destruction of the human-scale city for a high-density public housing.

The current zoning system has not helped the situation. Its overly complex character has allowed so much lawyerly manipulation in the interests of developers that we cannot assert that the current code protects the public interest. After all, in the code, air rights transfers and zoning lot mergers play the starring role of destroyers of neighborhoods and great urbanity. Sure, a hundred years ago the whole game may have seemed like reasonable policy because the public assets in questions seemed to be in limitless supply. But 100 years later our sense of scarcity of these public assets has changed. It should be obvious to anyone that we have reached a “tipping point” for the future of human-scaled urban neighborhoods. Thoughtlessly planned skyscrapers in a “death by a thousand cuts” process, now destroy once great street-level urbanity, and views, sky, and sunlight. This is happening throughout the city at a relentless pace.

One solution is height limits. They would protect ground level sunlight, our landmarks, our historic districts, and what is left of the human-scale parts of our city. Tourists who visit Midtown, Yorkville, and Wall Street may think there is no human-scale left in NYC, but we who live here know better. Yes, many areas are overbuilt, something we cannot undo, but there are many human-scale neighborhoods left. We can and should stop their destruction. Height limits can do that. And they need to be contextual to the historic fabric of each neighborhood, if only because we have such little fabric left. (A useful definition of historic fabric is anything built prior to 1945).

Another thing we must do is avoid the over-building mistakes of the past. We must continue to build, but first we need to plan, zone and build for a thick, more evenly distributed density of housing with a reasonable range of densities. And we must have public debate about what constitutes “reasonable” density. And a build-out of New York should be done with a vision of a contextual and human-scale design that includes the public realm and better sharing of our public assets. That means biting the bullet on building public transport out to areas now dependent on the car. And anyone who had thought about the logic of density for more than a minute knows that you don’t need skyscrapers to have increased density. Paris and Barcelona are dense cities of unsurpassed urbanity largely built out at around 7 stories. Neither do we need to have towers-in-the-park to have affordable housing: think of the famous examples of low-rise Marcus Garvey Village or the mid-rise Knickerbocker houses. A human-scale vision is realistic, but it would mean cutting our losses and confining our skyscrapers to limited areas, as has been done in many other cities.

Height limits will also remove the incentive to tear down historic fabric and will provoke a more equitable shift of real estate capital to other parts of the city, maybe even into the affordable and non-tower segments of the market. The private sector now treats that segment with contempt. Of course they do, since as an economic study recently cited, they can get 100% yield on capital by building high-rise luxury condos in already excessively dense areas. But their yield is literally dependent on taking for themselves the public assets of sunlight and views: developers get a 10% price premium for every unit that tops over the existing cornice line.[1] So the obvious public-interest solution is to change the game. And when we do that, and capital shifts in response to height limits, we will need to regulate the building so that it creates livable, human-scale neighborhoods of great rather than dreary urbanity, the historic districts of the future, not individual towers or ginormous mixed-use messes that serve big box stores, not local businesses.

Real Deal headlines over air rights transfers on what is left of imperiled South Street.

Developers will of course raise the hue and cry and try to scare us and say height limits will impede “growth.” But let me be clear: they are obfuscating. Height limits allow us a way to regulate real estate growth, not the economic growth of our society. Height limits will also protect our parks and gardens and street level light, and give us a way to fairly share what remains of our urban public assets after the thoughtless Bloomberg and De Blasio building booms. That is just part one of what needs to be done. Part two is that we must limit air rights transfers and zoning lot mergers. There are lots of ways to do that. We might say that air rights can’t be transferable at all. Certainly they shouldn’t float around the city from block to block or from river to waterfront. Another idea is to legislate better conservation easement tax advantages for individual property owners that equal the value of the air rights. Or, here is a good one: air rights transfers ought to trigger federal environmental impact statements that document the over-loading of the public realm, complete with threshold levels of that over-loading that can stop a project. Why not? The air rights market is not a “natural” and “free” market. Government created the air rights market by using the concept of a floor area ratios as a zoning tool. Air rights transfers are thus literally the child of government. Floor area ratios are thus not an entitlement, but a limit. Therefore, government can change them, take them away, and regulate them.

Changing the rules is always hard. Like fishermen of yore resisting rules on the catch, the real estate industry will always resist an attempt to rein in the social costs they impose and the free-for-all they have been used to. But rein them in we must. And step one is recognizing the public character of the assets of sunlight and air and views and the kinetic experience of great urbanity. Claim them and manage them. Then we can we build out New York in a way that honors rather than destroys the greatness already around us.

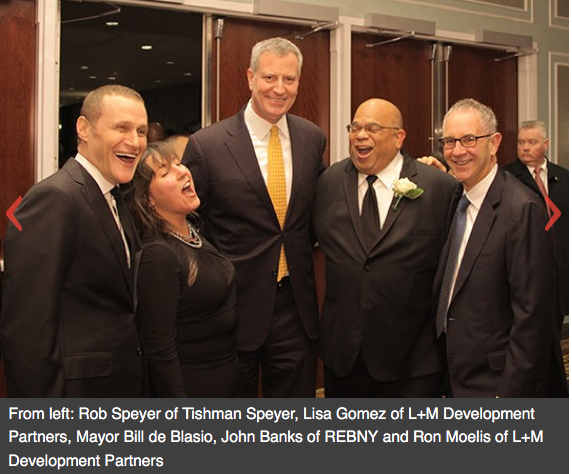

Source: Crain’s slideshow of the Mayor attending Big Real Estate’s Annual Gala 2016.

[1] See the spreadsheet annexes to the economic study the Department of City Planning commissioned over the “Mandatory Inclusionary Housing” proposal of 2015.

Chakrabarti, Vishaan. 2013. A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America.

Furman Center. 2015. “Creating Affordable Housing out of Thin Air.” Furman Center Research Brief, March.

Hardin, Garrett. 1968. “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Science 162 (3859): 1243–48. doi:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243.

Kent, Shia T, Leslie A McClure, William L Crosson, Donna K Arnett, Virginia G Wadley, and Nalini Sathiakumar. 2009. “Effect of Sunlight Exposure on Cognitive Function among Depressed and Non-Depressed Participants: A REGARDS Cross-Sectional Study.” Environmental Health 8 (July): 34. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-8-34.

Poteete, Amy R., Marco A. Janssen, and Elinor Ostrom. 2010. Working Together: Collective Action, the Commons, and Multiple Methods in Practice. Princeton University Press.

Sassen, Saskia. 2015. “Who Owns Our Cities – and Why This Urban Takeover Should Concern Us All.” The Guardian, November 24, sec. Cities. http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/nov/24/who-owns-our-cities-and-why-this-urban-takeover-should-concern-us-all.

Sunyer, John. 2013. “At Home (in Manchester) with Ian Simpson, One of the Architects Transforming the Face of London.” Financial Times, March 22.

![]()

That’s all for this week. Comments and corrections welcome. Sign the petition here.